Breaking the Silence I: The Wrath of Mdachi bin Sharifu

The traveling exhibition “Breaking the Silence I – The Wrath of Mdachi bin Sharifu” was shown from November 2018 to January 2019 as part of the overall exhibition “THE DEAD, AS FAR AS [ ] CAN REMEMBER” (curator: Felix Sattler) at the Animal Anatomical Theater TaT of the Humboldt University in Berlin. In September 2019, it was then moved to our colleagues from Kassel postcolonial (University of Kassel and Sandershaus). At the invitation of Entschieden gegen Rassismus und Diskriminierung e.V. we were able to present her from November to December 2019 at the University of Applied Sciences Bielefeld. From October 2020 to June 2021 it will be shown in cooperation with Decolonize Erfurt in the Small Synagogue Erfurt.

Introduction

Autumn 2017: We sit casually over a coffee with His Excellency Dr. Abdallah Saleh Possi, the Ambassador of Tanzania to the Federal Republic of Germany. We talk about our plans for an exhibition on the end of German colonial rule in East Africa 100 years ago. It is intended to critically examine the interwoven German-Tanzanian history and above all to commemorate the First World War, which was suppressed in Germany in what was then “German East Africa”.

After our explanation, the ambassador takes three old boxes out of the cupboard. They had been left at the embassy without comment before his term of office. Nobody remembers so exactly when and by whom. Inside are almost 250 historical photo plates made of glass. The majority of the pictures were, it seems, taken privately. One sees more or less clearly staged everyday situations from farm life in “Deutsch-Ostafrika”. Others show motifs that are familiar to us. They must have been added later. On many of them, one sees East African mercenaries of the German colonial regime.

After our explanation, the ambassador takes three old boxes out of the cupboard. They had been left at the embassy without comment before his term of office. Nobody remembers so exactly when and by whom. Inside are almost 250 historical photo plates made of glass. The majority of the pictures were, it seems, taken privately. One sees more or less clearly staged everyday situations from farm life in “Deutsch-Ostafrika”. Others show motifs that are familiar to us. They must have been added later. On many of them, one sees East African mercenaries of the German colonial regime.

Finally, the cabinet also contains an accompanying publication. Based on the diaries of plantation owner Karl Vieweg, his son Burkhard tells of his father’s experiences in the colony. It quickly becomes clear that it was precisely this settler who set up the slide collection between 1910 and his call-up to the “Schutztruppe” in August 1914. His son sees the loss of the plantation – his father’s “proud possession” – as an undeserved tragedy. For him, the colonial rule of the Germans in 1996 still represents a promising beginning of a well-meaning “development aid” for today’s Tanzania. He himself was active in this field for a longer period of time in the 1970s.

How to deal with such a collection, with this “heirloom”, which has now miraculously “returned” to the descendants of the colonized? How to work with an accompanying volume that is anything but a critical historiography? We have decided to show eight of the original glass plates in this first version of our exhibition, but to comment on them in detail. In doing so, we confront the colonial view of the photographers with the life experiences and voices of colonized people 100 years ago that are still marginalized today.

“His notes from eight years of experience in East Africa may also serve to counter the often heard claim that the colony was exploited by the Germans.” – Burkhard Vieweg on his father’s diaries, 1996

German “with reservations”

100 years ago, after the capitulation of German troops in East Africa on the 25th of November 1918, Germany’s colonial empire in Africa finally collapsed. When the Versailles Peace Treaty was signed at the end of June 1919, the colonies were formally ceded. Mandated by the League of Nations, in January 1920 the victorious powers of the First World War officially took control of the now independent republics of Cameroon, Togo, Namibia, Tanzania, Burundi and Rwanda. They legitimized this act with the excuse of the welfare of the colonized. According to American President Woodrow Wilson, the German empire proved itself to be a violent and incompetent colonial power, which “was more interested in the extermination of these peoples than in their development”.

In Germany this explanation of the Entente, which became known in the spring of 1919, provoked indignation and targeted counter propaganda almost throughout the political spectrum. “The heroic defence of the largest German colonies, German Cameroon and German East Africa” wrote the Deutsche Kolonialzeitung on the 20th of March 1919, ”would not have been possible without the faithful help of the natives; clear proof that Germany treated its coloured peoples fairly”.

Probably on the initiative of the government of the new German republic, Africans and Afro-Germans living in Germany also expressed their views on what was soon to be defamed as the “Kolonialschuldlüge” (colonial guilt lie). The migrants, most of whom came from Cameroon, came together for the first joint political action, an action which can be seen as the birth of the black community in Germany. On the initiative of the train conductor Martin Dibobe, who had been living in Berlin for over two decades, they handed over a petition dated the 27th of June 1919 to the government of the Reich. In this petition they actually spoke out, as the government wanted, in favour of Cameroon belonging to Germany. However, as a prerequisite for their consent to this agreement granted only “with reservations”, they named equality with white Germans in the newly established ‘social republic’.

The eighteen signatories to a comprehensive catalogue of 32 demands dealt bluntly with the Kaiser’s colonial regime and the colonial racism of Germany. They made clear not only their experiences with the horrific system of colonial oppression, but also protested against their lack of legal and societal recognition as German citizens, from which they were all affected. The Colonial Office of the Reich published a version of the petition that suppressed the central demands and that turned the spirit of the document into its opposite. The original text was then ‘misplaced’ by the colonial officials. However, one of the signatories, the teacher Mdachi bin Sharifu from “German East Africa”, did not accept this. Only a few weeks after the official loss of the German colonies, he addressed the general population through a series of lectures.

“Equality between Black and White shall be introduced.” – From the ,Dibobe Petition’, 27 June 1919

A free person, no longer a German African

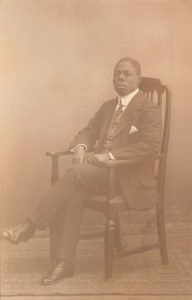

Mdachi bin Sharifu was born in 1885 close to Tanga. He attended the nearby government school, taught there himself later and went in 1907 to Songea, where he became a liwali (administrator). In 1913 the German colonial administration appointed him to the seminary for oriental languages in Berlin, where he and his colleague Halidi bin Kirama taught Kiswahili as ‘language assistants’. The world war brought both to a precarious situation. The return home became impossible and Africans from the colonies, who were already paid less than the other lecturers before the war, were now denied the inflation bonuses necessary for survival. After his assignment to teach he was sent to the Colonial Office of the Reich, where he had to carry out reception and translation work.

Sharifu and Kirama became politically active at the latest in the early summer of 1919. When the original petition of the Cameroonians, who co-signed them, is not published, Sharifu appeared on 16 August with the prominent pacifists Hans Paasche and Hellmuth von Gerlach of the New Fatherland Association as speakers in front of a broad audience. Under the title ‘Germany’s colonial past’, being provocative for those who were not at all willing to accept the colonies’ loss, he described in sometimes drastic words the “complaints of his people” and confirmed the brutal incompetence of the German colonial regime.

Three days later, Berlin’s first black orator gave up his position because he was no longer willing to be treated so “selectively disparagingly”- as though he were still a “German African” instead of a “free man”. Speeches in Hamburg and Erfurt followed, and the Seminar for Oriental Languages withdrew his pay. When he spoke once more in front of a German audience on the 19th of September 1919, he spoke about injustice in the German colonies as well as about the continued existence of an imperial spirit in the ministry and in the seminary.

Colonial officials who were present at the talks were beside themselves. In national conservative newspapers he was described and defamed by those who identified themselves as ‚old Africans‘ as a liar and a simple instrument of Bolsheviks and traitors. For the revisionist myth of Germany’s loyal colonial subjects, the chief witness Sharifu became a real danger. This is probably why the authorities now supported his return to British controlled East Africa. There he remained politically active: in 1929 he was a board member of the prominent Tanganyika African Association. According to its statutes it represented “the interests of Africans, not just in Tanganyika, but in all of Africa”.

„Either a rapprochement between Black and White in the interests of the whole of humanity or – the day will come – Africa for the Africans!“ –Mdachi bin Sharifu, 16. August 1919

Media Review

Deutschlandfunk, 8.11.2018 “Koloniale Gewalt und menschliche Überreste”

Frankfurter Rundschau, 10.11.2018 “Latentes Unbehagen”

Tagesspiegel, 19.11.2018 “Isaria Anael Melis Suche nach dem Schädel seines Großvaters”

Blog Uni Köln “Beziehungen kollaborativ kuratieren”

Kassel Postkolonial, 21.08.2019 “Ausstellung von Berlin Postkolonial in Kassel”